Free education is a popular idea that has gained traction in recent years, especially among progressive politicians and activists. The proponents of free education argue that it is the magical equalizer that provides opportunities opportunities for all people, regardless of their socio-economic backgrounds. They believe that education for all boosts the economy, reduces poverty, and increases social mobility.

Historically, access to quality education in Uganda was limited to the children of kings, chiefs, and other leaders, leading to low literacy rates and disparities in educational opportunities. The introduction of Universal Primary Education (UPE) in 1997 portrayed a pivotal shift towards prioritising basic education for all children. Government took on the ambitious goal of providing free primary education to all children in the country. This significantly increased access to education, particularly for marginalized and disadvantaged populations.

The introduction of Universal Primary Education (UPE) in 1997 portrayed a pivotal shift towards prioritising basic education for all.

The early 1990s also saw the emergence of private schools offering alternative educational options to parents seeking quality education for their children. I believe the policy makers of the time allowed for this knowing that UPE was not going to work.

The increased access from UPE, coupled with its automatic promotion policy increased the number of children completing primary education resulted in the increased demand for secondary education. In 2007, Uganda launched the Universal Secondary Education (USE) program.

The introduction of UPE and USE and the simultaneous growth of private schools in Uganda has led to a significant transition in the country’s education landscape. Being free and also compulsory for all citizens aged under 18, UPE and USE have proved to be the basic education provider of choice for majority of Uganda’s children.

Unfortunately, the implementation of free education in Uganda has over the years degenerated into a tool for political boast with less of the agenda to promote human capital development. 27 years later, Uganda continues to grapple with challenges related to illiteracy rates and disparities in educational opportunities. It is no surprise teachers, politicians and parents with the ability often opt for private schools; leaving UPE and USE for the financially incapacitated families and their “problem” child. To them, free education is indeed, but a scam. It easy to side with this parental bias and preference of private schools over free education on the grounds mentioned hereunder.

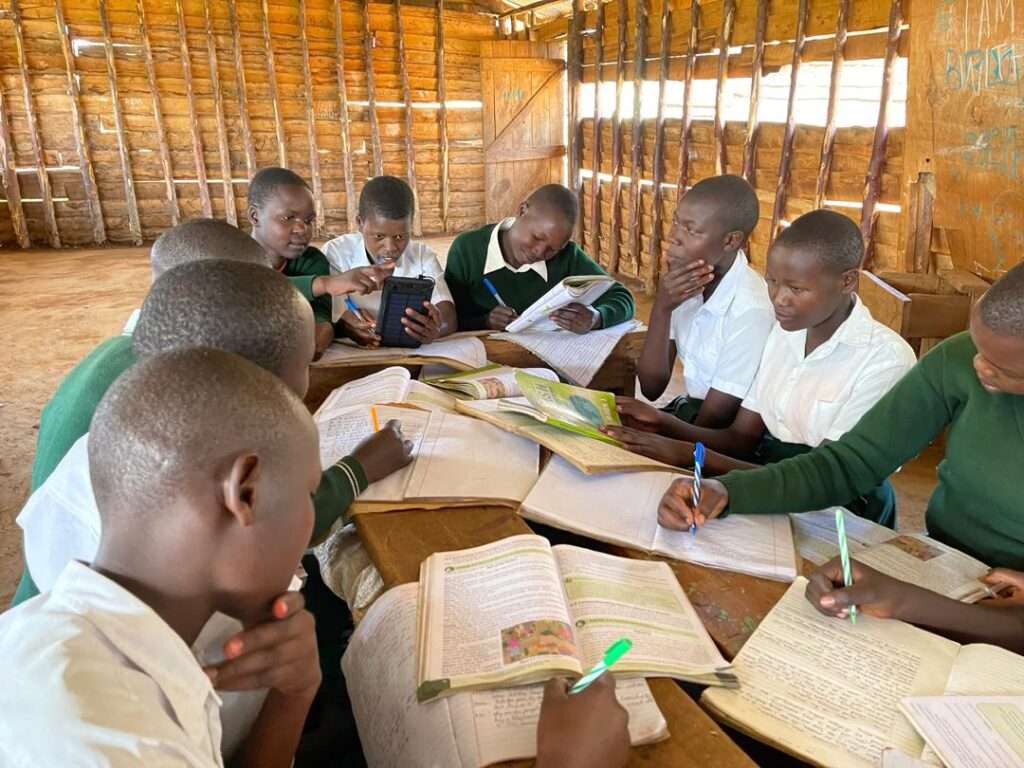

Free education in Uganda, has, by far lowered the quality of education. The manner in which it is being implemented has created a mismatch between supply and demand. With more students enrolling in secondary school, the resources available for each student have decreased, leading to larger class sizes for a small number of qualified teachers, hence less academic rigor. These programs are also characterized by reduced accountability of both educators and students who have no motivation to perform well or complete their studies.

Negligence has also cropped up among parents who now refer to their children as “Museveni’s children,” a notion that secretly advocates for the birth of more children especially in rural areas where the cost of living is comparatively lower. With the recently concluded census, we can only expect a significant increase in the fertility rate especially in rural districts across the country.

Sadly, free education in Uganda does not benefit the students who need assistance most, but rather subsidize the wealthier and privileged poor. In many schools, most of the benefits of USE go to comparatively better students, who are more likely to attend and complete UCE anyway. Their poorer colleagues continue to struggle with many barriers such as the lack of scholastic materials, mid-day meals, sanitary towels and uniforms and money for trips and fieldwork study. At home, these ones either hold several family obligations or are discriminated against. In the week that fees defaulters are sent home for money to facilitate such activities and programs, the class sizes even drop from 70 to only 3.

Free education strains the government budget and increases the tax burden on the public. In reality, “free education” is not really free, as someone has to pay for it. Currently, Uganda devotes a paltry 8.4 percent of its national budget to education, Out of this, government allocates Shillings 17,000 Ugandan per learner at the primary level and Shillings 56,000 for those in secondary school. With the withdrawal of world bank financing, Uganda will have to either raise taxes or cut spending on other public services in order to keep up with her educational programs like construction of seed schools that this donor has been financing.

Sadly also, the high dropout rates further exacerbate any projected return on investment and it can be deduced that free education would not necessarily lead to long-term savings or economic growth, as some advocates claim. When you have dropout rates as high as 50% and 60% for primary and secondary levels respectively, investment in free education is essentially wasted, as students are not completing their studies and obtaining the intended benefits. The overall return on investment and value generated remains very low. Project management experts will advise that the resources being allocated to free education programs with such completion rates could be redirected to other higher-impact initiatives that may generate greater social and economic returns.

No wonder, free education, as is in Uganda, is a scam that promises more than it can deliver. It lowers the quality of education, benefits the wealthy and privileged at the expense of the poor and marginalized, and impose a heavy financial burden on the government and taxpayers. Rather than pursuing this unrealistic and harmful idea, policymakers should focus on improving the quality and affordability of education for all students, especially those who face the greatest challenges and have the most potential. Alternatively, if its implementation is rethought and politicians learn to speak the same language with implementers, free education and increased access can yield equal opportunity, economic growth and social mobility.

If implementation is rethought and politicians learn to speak the same language with implementers, free education can yield for Ugandans equal opportunity, economic growth and social mobility.

Your point is that the initiatives (USE and UPE) are fundamentally flawed and have negative consequences rather than positive outcomes.

There is a need to further explore the broader ideological and practical advantages of free education. While tackling immediate obstacles and implementation challenges, we might be missing out on the enduring benefits and transformative power of guaranteeing education for all.

Acknowledging Uganda’s historical exclusion of marginalized groups from quality education is important, but we should also acknowledge the significant shift that UPE and USE represent. Prior to these programs, education was a privilege for the elite only. The introduction of free education policies aimed to democratize access, opening doors for millions of children who were previously deprived of such opportunities. This shift towards inclusivity should not be underestimated.

Although you’ve rightly pointed out issues like overcrowded classrooms and inadequate resources, these are implementation challenges rather than inherent flaws in the concept of free education itself. The identified problems—such as lack of funding, insufficient teacher training, and poor infrastructure—can be resolved through improved policy measures and increased investment. Blaming free education for these shortcomings is akin to blaming democracy for poor governance; the real issue lies in execution rather than in principle.

It is misleading to assert that free education primarily benefits wealthier students while widening socio-economic gaps. While affluent families may supplement their children’s education, the main beneficiaries of UPE and USE are indeed marginalized populations. For many children from impoverished backgrounds, free education is their only pathway to literacy and essential skills. Instead of giving up on free education altogether, efforts should focus on addressing the barriers faced by disadvantaged students by providing meals, educational materials, and support for family obligations.

Suggesting that free education leads to parental neglect oversimplifies matters. Education is a joint responsibility shared between the state and families. Rather than viewing children merely as “Museveni’s children,” parents should be encouraged to actively engage in their children’s learning journey. This necessitates community involvement and awareness programs to instill a sense of collective responsibility. Holding parents accountable for policy shortcomings overlooks the systemic issues that demand attention.

Critics often argue that free education strains government budgets and increases tax burdens without realizing that education is an enduring investment in human capital. Educated individuals are more likely to contribute positively to the economy, foster innovation, and propel societal advancement.

The advantages of having a well-educated populace far exceed any costs associated with it, even if those benefits are not immediately visible. Strategic international partnerships along with efficient resource allocation can help alleviate financial pressures.

Blaming dropout rates solely on free education ignores deeper socio-economic complexities requiring comprehensive solutions addressing factors like poverty, early marriages, and child labor instead. Targeted interventions can effectively reduce dropout rates ensuring students complete their schooling successfully.

Education stands as a fundamental human right crucial for individual empowerment as well as societal progress. Guaranteeing every child access to quality education transcends mere economic considerations; it embodies a moral obligation rooted in justice, equality, and belief in every child’s potential realization.

Focusing on immediate challenges while disregarding the long-term gains and transformative possibilities brought forth by these initiatives could hinder progress.

Through addressing implementation challenges and investing in necessary resources, Uganda can unlock the true potential promise embedded within free education ideals. Rather than forsaking this vision entirely, policymakers should strive towards refining its execution ensuring all children irrespective of their socio-economic status have equal access to quality education unlocking boundless opportunities it affords.